Pacemakers are implanted to help control your heartbeat. They can be implanted temporarily to treat a slow heartbeat after a heart attack, surgery or overdose of medication. Pacemakers can also be implanted permanently to correct a slow heartbeat (bradycardia) or, in some cases, to help treat heart failure. To understand how a pacemaker works, it helps to know how your heart beats.

How your heart beats

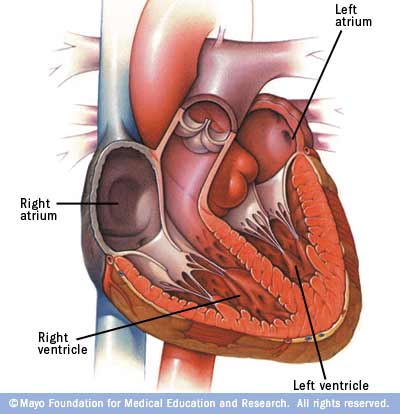

The heart is a muscular, fist-sized pump with four chambers, two on the left side and two on the right. The upper chambers are the right and left atria. The lower chambers are the right and left ventricles.

For your heart to function properly, the heart's chambers must work in a coordinated fashion. Your heart must also beat at an appropriate rate — normally from 60 to 90 beats a minute in resting adults. If your heart beats too slowly or too rapidly, not enough blood flows through your body, leading to fatigue, fainting, shortness of breath, confusion, and other signs and symptoms.

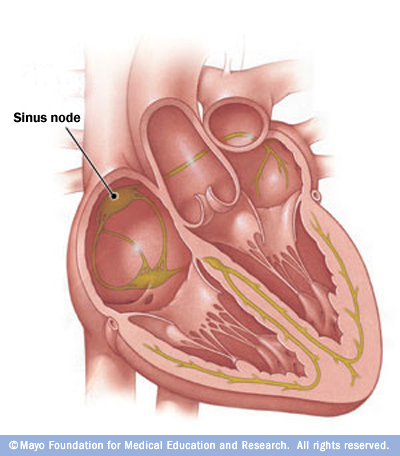

Your heart's electrical system controls the chambers' pumping action. A normal heartbeat begins in your right atrium, in the sinus node. This cluster of cells — your natural pacemaker — acts like a spark plug, generating regular electrical impulses that travel through specialized muscle fibers.

When an electrical impulse reaches both the right and left atria, they contract and squeeze blood into the ventricles. After a split-second delay to allow the ventricles to fill, the impulse reaches the ventricles, making them contract and pump blood to the rest of your body.

What a pacemaker does

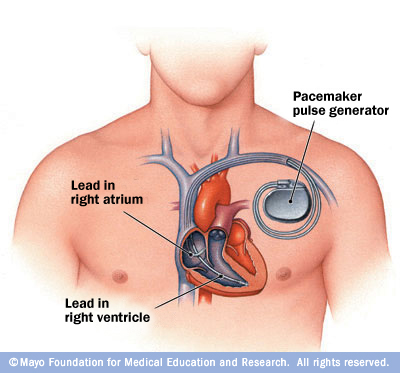

An implanted electronic pacemaker mimics the action of your natural pacemaker. An implanted pacemaker consists of two parts:

-

The pulse generator. This small metal container houses a battery and the electrical circuitry that regulates the rate of electrical pulses sent to your heart.

-

Leads (electrodes). One to three flexible, insulated wires are each placed in a chamber, or chambers, of your heart and deliver the electrical pulses to adjust your heart rate.

Pacemakers monitor your heartbeat and, if it's too slow, the pacemaker will speed up your heart rate by sending electrical signals to your heart. In addition, most pacemakers have sensors that detect body motion or breathing rate, which signals the pacemaker to increase your heart rate during exercise to meet your body's increased need for blood and oxygen.

Single-chamber pacemakers

These types of pacemakers usually carry electrical impulses from the pulse generator to the right ventricle of your heart.

Dual-chamber pacemakers

Dual-chamber pacemakers carry electrical impulses from the pulse generator to both the right ventricle and the right atrium of your heart. The impulses help control the timing of contractions between the two chambers.

Biventricular pacemakers

Biventricular pacemakers are a treatment option for people with heart failure whose hearts' electrical systems have been damaged. Unlike a regular pacemaker, a biventricular pacemaker stimulates both of the lower chambers of your heart (the right and left ventricles) to make the heart beat more efficiently. A biventricular pacemaker paces both ventricles so that all or most of the ventricular muscle pumps together. This allows your heart to pump blood more effectively. Because this treatment resets the ventricles' pumping mechanism, it's also referred to as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT).