An average C-section can usually be done in less than an hour. In most cases, your spouse or partner can stay with you in the operating room during the procedure.

-

At home. You might be asked to shower or bathe with an antibacterial soap the night before and the morning of the C-section. This helps reduce the risk of infection. If you regularly shave your pubic hair, don't do it the day before your operation.

-

At the hospital. Before your C-section, a member of your health care team will cleanse your abdomen. A tube (catheter) will likely be placed into your bladder to collect urine. Intravenous (IV) lines will be placed in a vein in your hand or arm to provide fluid and medication. A member of your health care team might also give you an antacid to reduce the risk of an upset stomach during the procedure.

-

Anesthesia. Most C-sections are done under regional anesthesia, which numbs only the lower part of your body — allowing you to remain awake during the procedure. A common choice is a spinal block, in which pain medication is injected directly into the sac surrounding your spinal cord. Another option might be epidural anesthesia, in which pain medication is injected into your lower back just outside the sac that surrounds your spinal cord. In an emergency, general anesthesia is sometimes needed. With general anesthesia, you won't be able to see, feel or hear anything during the birth.

-

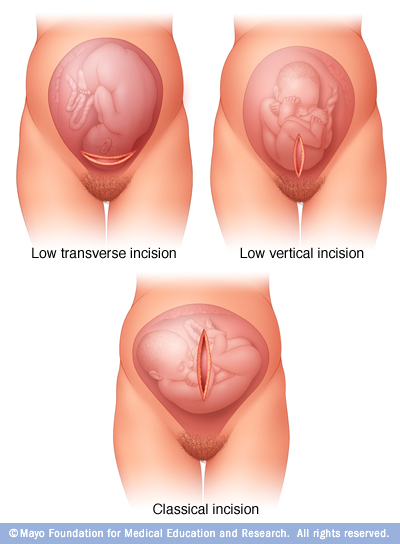

Abdominal incision. The doctor will make an incision through your abdominal wall. It's usually done horizontally near the pubic hairline (bikini incision). If a large incision is needed or your baby must be delivered very quickly, the doctor might make a vertical incision from just below the navel to just above the pubic bone.

-

Uterine incision. After the abdominal incision, the doctor will make an incision in your uterus. The uterine incision is usually horizontal across the lower part of the uterus (low transverse incision). Other types of uterine incisions might be used depending on the baby's position within your uterus and whether you have complications, such as placenta previa — when the placenta partially or completely blocks the uterus.

-

Delivery. If you have epidural or spinal anesthesia, you'll likely feel some movement as the doctor gently removes the baby from your uterus — but you shouldn't feel pain. The doctor will clear your baby's mouth and nose of fluids, then clamp and cut the umbilical cord. The placenta will be removed from your uterus, and the incisions will be closed with sutures.

If you have regional anesthesia, you'll be able to hear and see the baby right after delivery.

After the procedure

After a C-section, most mothers and babies stay in the hospital for about three days. To control pain as the anesthesia wears off, you might use a pump that allows you to adjust the dose of intravenous (IV) pain medication.

Soon after your C-section, you'll be encouraged to get up and walk. Moving around can speed your recovery and help prevent constipation and potentially dangerous blood clots.

While you're in the hospital, your health care team will monitor your incision for signs of infection. They'll also monitor your movement, how much fluid you're drinking, and bladder and bowel function.

Discomfort near the C-section incision can make breast-feeding somewhat awkward. With help, however, you'll be able to start breast-feeding soon after the C-section. Ask your nurse or the hospital's lactation consultant to teach you how to position yourself and support your baby so that you're comfortable.

Remember that trying to breast-feed when you're in pain might make the process more difficult. Your health care team will select medications for your post-surgical pain with breast-feeding in mind. Continuing to take the medication shouldn't interfere with breast-feeding.

Before you leave the hospital, talk with your health care provider about any preventive care you might need, including vaccinations. Making sure your vaccinations are current can help protect your health and your baby's health.

When you go home

It takes about four to six weeks for a C-section incision to heal. Fatigue and discomfort are common. While you're recovering:

-

Take it easy. Rest when possible. Try to keep everything that you and your baby might need within reach. For the first few weeks, avoid lifting from a squatting position or lifting anything heavier than your baby.

-

Support your abdomen. Use good posture when you stand and walk. Hold your abdomen near the incision during sudden movements, such as coughing, sneezing or laughing. Use pillows or rolled up towels for extra support while breast-feeding.

-

Drink plenty of fluids. Drinking water and other fluids can help replace the fluid lost during delivery and breast-feeding, as well as prevent constipation.

-

Take medication as needed. Your health care provider might recommend acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) or other medications to relieve pain. Most pain relief medications are safe for women who are breast-feeding.

-

Avoid sex. Don't have sex until your health care provider gives you the green light — often four to six weeks after surgery. You don't have to give up on intimacy in the meantime, though. Spend time with your partner, even if it's just a few minutes in the morning or after the baby goes to sleep at night.

It's also important to know when to contact your health care provider. Make the call if you experience:

-

Any signs of infection — such as a fever higher than 100.4 F (38 C), severe pain in your abdomen, or redness, swelling and discharge at your incision site

-

Breast pain accompanied by redness or fever

-

Foul-smelling vaginal discharge

-

Painful urination

-

Bleeding that soaks a sanitary napkin within an hour or contains large clots

-

Leg pain or swelling

Postpartum depression — which can cause severe mood swings, loss of appetite, overwhelming fatigue and lack of joy in life — is sometimes a concern as well. Contact your health care provider if you suspect that you're depressed. It's especially important to seek help if your signs and symptoms don't fade on their own, you have trouble caring for your baby or completing daily tasks, or you have thoughts of harming yourself or your baby.